Rafat Siddiqui’s journey to motherhood began eight years after her life-altering accident in 2010. In this interview, she talks about her supportive family, the special bond that she shares with her husband, embracing motherhood and her daughters who mean the world to her

…..

Swati Subhedar

“It was a miracle. I asked my husband to buy me a pregnancy kit. In my head, I knew the test was going to be negative, but, in my heart, I was hoping for it to be positive. Those few minutes were the longest of my life. The result made me numb,” said Rafat Siddiqui, 35, who has been in a wheelchair for the past 10 years after meeting with an accident in 2010 that seared her spine.

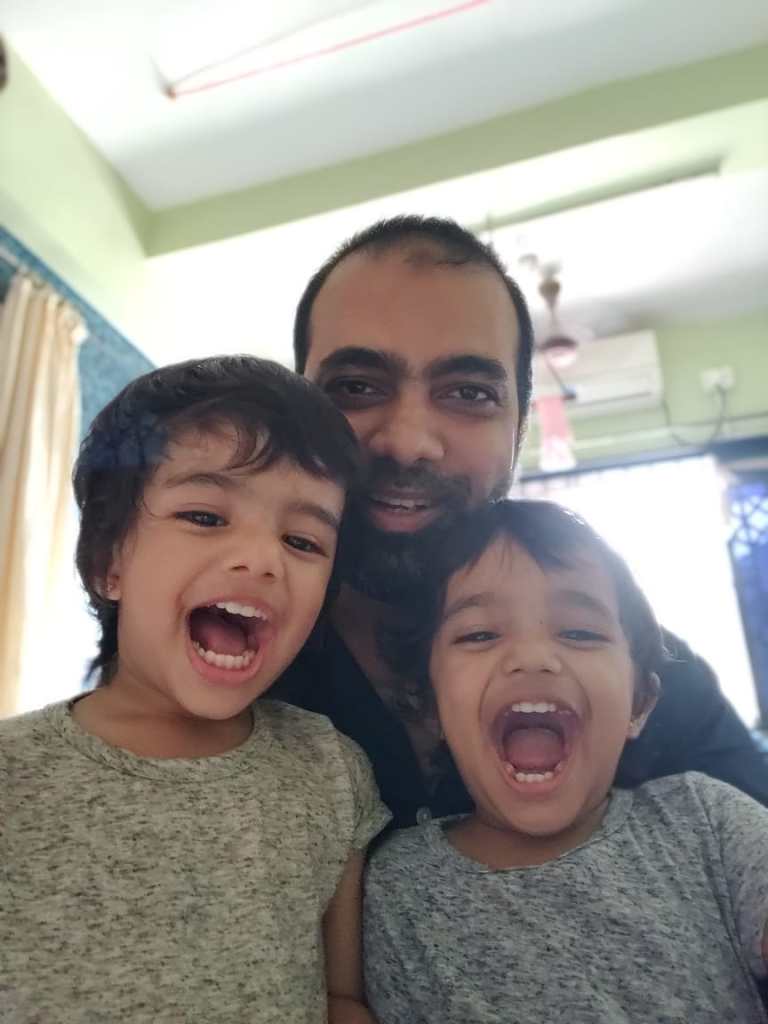

Given her condition, she knew the pregnancy was going to be tough on her, but her little babies would kick her and they gave her the strength to carry on with the painful nine months. Born prematurely, her twin daughters were too fragile and tiny and were moved to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) even before she could touch them. When she held her daughters, Fatima and Safiya, for the first time after 10 days, she whispered to them: “I am your Amma, and you are my girls.”

Rafat was just 25 when she met with the accident. She had been married for two years then and life was full of love, hope, and dreams. Being confined to a wheelchair was tough. Being dependent on others for basic needs was heart-breaking. However, the incredible support that she got from her family, especially her husband, gave her the strength. “My husband is my spine, and my daughters are the miracle that completes my life,” she said.

The daughters are two-year-olds now. “There was a time when they were so tiny that they would fit in my husband’s palm. Now, it’s difficult to catch hold of them. They say ‘a child gives birth to a mother’. It’s so true. From the time they have entered my life, even before they were actually born, there’s nothing that’s more important than them,” she said. In this story, she talks about these special bonds.

When an ill-fated moment changed her life

Rafat, the eldest among the three siblings, was born in Nagpur but grew up in Mumbai. Her parents managed to give them a wonderful life. She got everything that she wanted, except for a Scooty, which she had been asking for since she turned 15. She graduated, took up a part-time job, and even did a computer course, in a hope that her parents would buy her a Scooty, but that did not happen.

At 23, she got married. Like a typical Mumbai girl, she juggled between her job and managing her house. She loved her routine — wake up early, prepare breakfast and lunch for all, finish household work, go to the office in a crowded Mumbai local train, come back in the evening, have a cup of coffee, chit-chat with her in-laws, and then prepare dinner for all. She would happily spend most of her Sundays in the kitchen cooking something special for her family. The accident changed everything.

In 2010, around the time she met with the accident, she had taken a break from her work to make arrangements for her brother-in-law’s wedding. The house was buzzing with activities, there was a lot of shopping lined up and the house was being renovated. The silver lining for her amid all the craziness was that she was given a Scooty to run errands.

One day, she had to accompany her husband to his office. There was a lot of traffic, but it had cleared by the time she was returning. This time, her sister was accompanying her. Suddenly, she fell off her Scooty – just like that. They were driving slowly, carefully, there was no traffic, they didn’t bump into anyone, no one hit them from behind. And yet, she fell off. Strangely, there was not a single scratch on the vehicle, and her sister was unhurt too.

Of confined life and strengthening bonds

She was taken to a hospital as she had multiple bruises and concussions. After several tests, scans, and MRIs, the family was informed that she had also suffered a spinal cord injury … “That’s how she is going to be. Neck down, no movement, no sensation.”

Her family, especially her husband, was very supportive. “When the doctor informed him about my injury, my husband asked him to carry on with the treatment and said he would be by my side all my life irrespective of whether I was going to be in a wheelchair or confined to a bed. After I was discharged, my father arranged for therapists for me,” she said.

The therapy sessions were painful, but after three to four months, she could at least move her neck, fingers, and had trunk control. The family even opted for Stem Cell Therapy treatment. They first went to a private hospital but found the treatment to be too costly. Then they went to Sion Hospital, (a government hospital in Mumbai). “I was only six months into the injury. The doctors tried to accommodate me saying my body may show a good response. It was a difficult process. I spent two days at the hospital and had to do a lot of exercises after returning. I am not in a position to say if the Stem Cell Therapy treatment was 100% effective, but after six months there was a little sensation in my body. I could take baby steps with the help of a calliper and a walker,” she said.

However, there were setbacks. “I got a foot nail ingrowth, which was quite deep. It resulted in my body to fall back. I had to start all over again. Every time my body showed some improvement, I had to stop because of pressure sores or weakness or some other reason. That became my life then,” said Rafat.

She moved back to her in-laws’ place and hired an attendant. She started working as a freelance content writer, which boosted her confidence. She also started meeting others who were dealing with spinal cord injuries, which motivated her further. Life, however, in her own words, had become very monotonous. It was her husband who played a key role in keeping her happy and motivated. He would take her to malls and they would often go out to eat paani puri.

When asked if the bonding between them has strengthened after the accident, she said: “It’s been more than 10 years, but my husband has never mentioned my condition to me. In fact, he shuts all those around me who say hurtful things, or pull me down. We have been married for 13 years, so we have had our share of ups and downs, but one thing I can say with full conviction is that my husband is my spine. Alhamdulillah, he’s one of the choicest blessings from the Almighty.”

She believes that nothing stops persons with disabilities from being good partners. “When someone accepts a person with a disability as a partner, that relationship is very special. Yes, there is love, but there is also a lot of understanding. They are a lot more patient and they care about each other a lot. The whole chemistry between them changes as they know that life is going to be more demanding, and full of sacrifices,” she said.

Embracing motherhood

In 2017, Rafat went on a pilgrimage to Mecca along with her family. The trip was special as it was her first long-distance travel after the accident. After returning, the couple came to know about the miracle.

“Frankly, it just happened out of the blue. Considering my physical condition, the amount of pain and spasms, and involuntary movements in my body, my husband would avoid making any close contact with me as he didn’t want me to go through the pain. However, the Almighty was happy with us and wanted us to experience parenthood. When the pregnancy test came positive, we were too shy to disclose it. Also, we wanted to be completely sure before we could reveal it to our families,” she said.

The first visit to the doctor was crucial as they had to weigh all the pros and cons given her condition and the effect the pregnancy was going to have on her mind and body. It was decided that they would “take a call” if it was going to take a toll on her health. But Rafat was not in a mind to take any such call. She had decided she wanted to be a mother.

She was aware that carrying twins was never going to be easy. “I had to stop all my medicines. I couldn’t exercise. I would be sick all day and all night long. I wouldn’t talk much. I couldn’t sit properly. I would feel uncomfortable if I would lie down for too long. I would have severe mood swings. There were typical pregnancy issues like vomiting, dizziness, breathlessness, and BP,” she said, adding: “It worsened as the babies grew. There were days when I couldn’t even take the smell of food. Managing my bowel and bladder was another challenge. It was taking a toll on my body, but my babies kept kicking me, reminding me to be strong and positive.”

Being a mother

The babies arrived before the due date and were underweight and quite fragile and were moved to the NICU. “I couldn’t enter the NICU because of the wheelchair and as men are not allowed inside a NICU, my husband couldn’t see them either. They were just 1.4 kgs when they were born. Now they weigh 11 kgs and the credit goes to my parents and siblings. Their feeds, massages, naps, baths, crying and tantrums … my parents handle everything. It does get overwhelming at times with all the sleepless nights and days, anxiety and palpitation, tears and fears, struggle and losses, sacrifices, and compromises. Not just for me, for everyone. But my daughters are the apples of my eyes and my source of energy. They are the miracle that makes my life complete,” said Siddiqui.

This is Part 3 of our series ‘Unbound’ – a spinal cord injury awareness series. Read Mrunmaiy’s story, Ishrat’s story Garima’s story Preethi’s story, Suresh’s story, Kartiki’s story, Ekta’s story.